"A man who does not smoke or drink will die healthy," Mishka Zaslavsky quotes a well-known Odessa proverb with a chuckle. He began his morning with a small glass of vodka, but he quit smoking 30 years ago, because of the health risk. He can climb up and down the 80 steps to his fifth-floor apartment in the Cheriomoshka neighborhood in Odessa with relative ease. Impressive, because he is 93 years old.

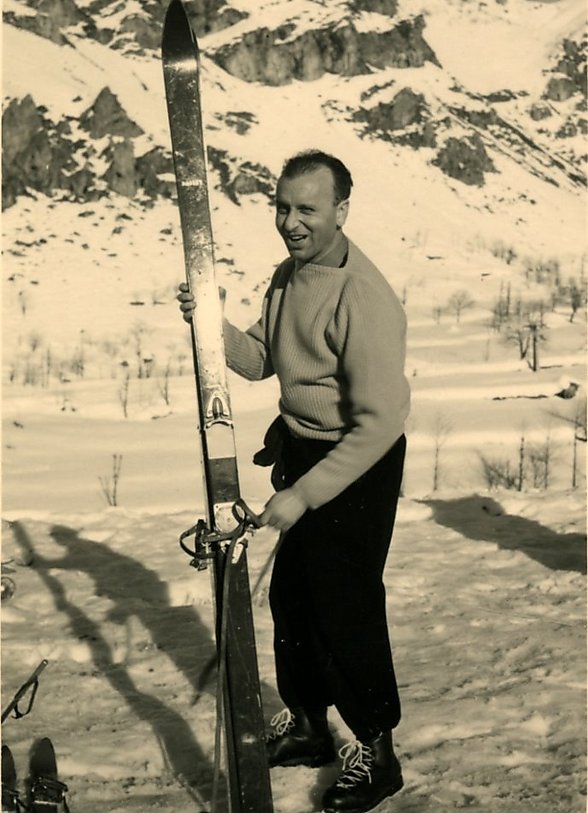

It is bitterly cold outside—minus 14 degrees. A thin layer of snow covers the back yards of destitute Soviet-era homes. Zaslavsky politely refuses everyone who extends a hand to help and climbs into the high car by himself. A year ago, he adopted a new look that gives him charm and attractiveness. "I'm young," he laughs and he runs his hand through his white ponytail. "Today, young men are growing out their hair." Despite the style, he is not young, but his mind is sharp, fresh, and refuses to be despondent.

He was born in Odessa in October 1925. His mother Miriam, who was raised in a deeply religious home, summoned the mohel twice. Twice, his father, Abraham, sent the mohel back from whence he came. He refused to have his eldest son circumcised, because he had abandoned religion following the horrors of the First World War. The father's stubbornness saved his son in the Second World War.

Mishka Zaslavsky at the monument for Odessa's Jews

"I was 16 when the Nazis conquered Odessa," related Mishka. "Dad was drafted into the Red Army, and my mother, with five small children, could not escape to the east. On October 16, I saw my first Nazi soldier."

At the time, Odessa was known as an important center of Judaism and Zionism. 100,000 of the city's Jews were able to escape before October 16, 1941, when the German army and their Romanian allies captured the city. About 90,000 Jews were still in the city. Odessa was severed from Ukraine, then a part of the Soviet Union, and declared the capital of Transnistria, territory that Hitler ceded to Romania. The Einsatzkommando, a Romanian intelligence company, and local Ukranian militias succeeded in murdering more than 10,000 Jews in the first few days of the occupation.

"On October 19, a soldier came to our house and told us to get ready within 20 minutes. I remember my mother's helplessness. How are you supposed to pack for five children in 20 minutes? We went outside with my younger siblings and a few baskets. All the Jews were removed from the adjacent buildings, and we were collected together, about 3,000 people, overnight, at the school. In the morning, we were taken from there, escorted by barking dogs and murderous blows, to the city's central prison."

The prison, built of red bricks during the Tsarist era, still stands in the heart of Odessa. During a tour of the city, Mishke points to it and to the route they marched. "There was a very long line, mostly women, children, and the elderly," Mishka remembers. "It was hot. Locals watched the scene from both sides of the street. There were women who wept, but there were those who stole objects and shouted, 'You deserve it, zhids!' At the prison, 18 people were put in cells meant for one. No food or water were brought to us. I remember the women's cries of terror."

Numerous testimonies tell of women and girls who were taken from the cells to the prison roof, where they were brutally raped by Romanian soldiers.

On October 22, the Romanian HQ was blown up, apparently by a mine that was planted there by the Soviets before the German-Romanian occupation. The blast killed 66 military personnel and the city's military governor. In response, the Romanian ruler, Marshal Ion Antonescu, ordered the execution of 200 communists for every officer killed and 100 for every enlisted man. In Nazi-Romanian eyes, communists meant Jews. About 5,000 Jews were shot that same day, and thousands of them were hanged in main city streets, left there for several weeks. The hangings are etched into the memories of every survivor we met, even those who were only young children at the time.

The hangings and abuse did not diminish the Romanians' fury. "The next day, October 23, they took us from the prison in a convoy for several kilometers to the munitions bunkers," Mishka remembers. "We walked very slowly. Every time we stopped, the elderly were beaten. It is hard to remember. When I remember, I weep," he says, dropping for a moment his tough façade to wipe away the tears that well up in his blue-grey eyes.

"I walked with my five-year-old brother Alik on my shoulders. Mom carried the one-year-old Hanna, and two sisters, Yava and Zhenia, walked with an aunt. The moment we reached the gate in the bunkers' fence, I felt someone yank Alik from me. I tried to hold onto him, but I was beaten and shoved. The few men and youths, together with wounded prisoners of war, were put into the farthest bunker and separated from the women and children. There were high guard towers with soldiers. The Romanians brought trucks with fuel tanks and sprayed the outside of the bunkers with gasoline."

22,000 Jews and wounded prisoners of war were put into the huge bunkers, which had been built in the Tsarist era on the edge of the city. So far as is known, all were burned alive, except for Mishka.

"The fire took hold of the roof and burned a hole through it. I began to push and climb up. I've been told that it is not nice to say that I shoved (people), but that's the reality. I shoved and everyone else shoved, too. A few more men and youths were able to get out of the bunker and climb the fence. The roar of the fire was incredible. It was terrifying. I jumped over the fence. The soldiers in the guard towers began shooting at everyone who fled. They didn’t hit me. I jumped into a cornfield and crawled. I could not help but look back. What did my one-year-old sister do to deserve to die like that?"

By November 3, 1941, Odessa's remaining 40,000 Jews were gathered into the Slobodka Ghetto. After wandering around, Mishka also ended up there. Later, Jews from the ghetto were sent out to bury the burned corpses.

Mishka escaped from the ghetto, and used forged papers to survive for a long time as an employee of the city's power station.

"Every time someone suspected I was a Jew, I showed the natural identity card that was left on my body thanks to my father. That is how I survived," he says, referring to the fact he was uncircumcised.

Later, after someone informed on him, he was arrested and forced to admit his true identity. He was sent back to prison.

He escaped with the help of an Ukranian woman who brought him food when he was put to work cleaning streets outside the prison. He nicknamed her "Aunt Mora," and she hid him in her home.

On April 10, 1944, when he was 18.5, the Red Army liberated Odessa. Mishka immediately decided to enlist. "I could have stayed in Odessa, but I wanted to avenge the death of my family. We were given new uniforms and underwent training," he explains.

Just before being sent to the front, his father found him, having returned from the battles to the family home, where he found strangers living. "Dad found me. We hugged and I told him everything. We smoked a cigarette together; I was already a man, not a boy. We both cried. That was it. We had to go forward."

His father stayed in Odessa to live with an aunt, and Mishka went to the front. He helped liberate six countries and reached Berlin. He was wounded twice by bullets, once in the right leg and once in the left.

"And they say the Jews did not fight," he complains, pulling a jacket heavy with medals from the closet. "The Red Army did not always treat the Jews well, calling them traitors."

Zaslavsky with his long hair and medal-laden jacket

When he returned home, he married Ira, who passed away 28 years ago. He led a full life in Odessa working as an electrician and raised a family.

There are no other survivors known from the massacre in Odessa, except for Mishka. Detailed documentation of the mass burning can found in official Romanian documents. During the Soviet era, a neighborhood was built over the site of the bunkers. The sole commemoration of the atrocity was a small monument with general text about the killing of Soviet citizens by the Nazis.

"Shameful. It would have been better to say nothing. We argued with the authorities. We demanded to move a building and a utility pole. In the end, the area was excavated and the mass grave was found," he says, pointing to the plaza around the new monument. "The entire neighborhood is built on bones. We ultimately raised money and built a proper monument here."

Mishka's "we" is the Odessa Holocaust Survivors Organization, which was founded in 1990 by 2,500 survivors and 170 non-Jews who were recognized as Righteous Among the Nations for their efforts to save Jews during the Holocaust. Today, 340 survivors are still alive in the city, mostly children who survived in hiding, and eight Righteous non-Jews.

The survivors and rescuers jointly built a fairly unknown museum, which relates the story of the Holocaust in Odessa. The museum includes a model of the burning bunkers.

"The government gave us a very dilapidated building," says Mishka. "I was already 80, but I personally broke walls, and, as an electrician, built the museum with my comrades. I was a member of the management team for over a decade. All of us donated money for the museum to open and for free entry. Most of the survivors struggle financially, especially now given the crisis in Ukraine. But we'd sell our clothes so the museum can continue to operate. I recently resigned and passed the baton to younger survivors.

"Every year, on January 27, International Holocaust Day, we organize a ceremony in the park were the Jews were assembled before being sent on death marches. Over the past five years, since the day was declared by the UN, the Odessa Municipality has finally participated in the ceremony as well. We won't let it be forgotten. That is why we are here."

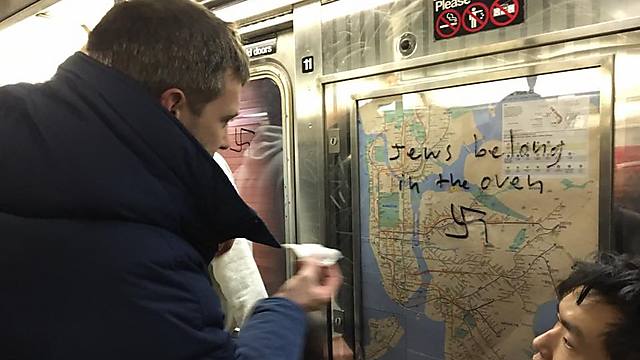

The museum, like many other Jewish institutions in the city, is a target for anti-Semitic vandalism. When the glass windows were broken, they were replaced with metal ones. Neo-Nazi slogans in the "Jews out" style are spray-painted near the museum regularly.

Over the generations, most Ukranian Jews took the hint and chose to leave. But many still remain, mostly elderly and childless. About 180,000 elderly Jews, many of them Holocaust survivors, live all over the former Soviet Union. Not much is left of the welfare system of the communist regime that once ruled there and the elderly live on meager pensions.

Although Holocaust survivors recognized by the Claims Committee receive financing from the German government and Swiss banks, it is not enough to live on because of the economic crisis and soaring electricity and water rates. Today, Ukraine is the poorest of the former Soviet republics, because of the civil war in the east.

A number of organizations are trying to help them, including the International Fellowship of Christians and Jews, which hosted me in Odessa. Through the American Jewish Joint Distribution Committee and Chabad, the fellowship currently helps about 17,000 Holocaust survivors in Ukraine, providing security, distributing food and medicines, organizing community activities, and offering individual home care for the elderly.

"I don’t know if Israel or Jewish communities around the world understand how difficult the conditions are. Something must be done," says International Fellowship of Christians and Jews President Rabbi Yechiel Eckstein.

"Over the years, I have made countless visits to Ukraine and elsewhere, and I was horrified by the distress. Many Jews live in remote villages that take five hours to reach because the roads are blocked and unfit for travel. There are survivors who live on the fifth floor without an elevator. Most people in these circumstances simply don’t leave their homes for years. Many survivors live in utter isolation and really depend on us and our partners for their basic needs, such as food and medicine. We raise about $25 million a year from Christians in the US who want to help Jews from one of the largest communities in the world, which is also one of the poorest in the world.

"It hurts me that Jewish communities that thrive in the US, Israel, and elsewhere donate very little to this endeavor. There are about 70,000 elderly Jews in former Soviet republics that no organization has yet reached, because there isn’t enough money. This situation is shameful on the Jewish people. On International Holocaust Remembrance Day, it is important to remember other holocausts, but no less important to strive that the remaining survivors can live out the rest of their days with dignity."

Mishka is lucky in that he can still live with dignity. For our meeting, he allows himself to play the actor, like his grandfather. "Before the revolution, my grandfather was in the Jewish theater in the shtetl. He wrote and sang songs in Yiddish and Russian."

Mishka stood up and began to sing in Yiddish, "I dream of the day when Jews can be free like all people."

Jews are free in Israel. Why didn’t you make aliyah?

"My homeland is here. There are good people here like Aunt Mora," he shouts. "There are good and bad people everywhere. I choose to believe in the good people. No one can remove me from here. My victory over the Nazis is my four Jewish great-grandchildren. But I won't leave here. If I go, who will protect the bones of my family?"

Let's block ads! (Why?)

The only Jew to survive the 1941 Odessa massacre : http://ift.tt/2nzu6NE