Our meeting was arranged by Rabbi Ari Edelkopf, who upon hearing our interest in Montenegro’s story informed us that what we sought was a 72-year-old man named Jasa who will be pleased to travel an hour to meet us. And he did.

Who, upon first introduction, admonishes his new acquaintance with a warning that “you no doubt are opposed to cigarette smoking, but I’m not stopping?” In the very first minutes of our conversation a distinct melding of the great strength that clearly served him well as he pursued classified security missions for the state of Israel and a loving persona that made his lost flock a personal responsibility that would consume the remainder of his days. Prior to his sudden death, Jasa had single-handedly identified and contacted each Jew living in Albania, Kosovo and Montenegro, worked with the government of Montenegro to have Judaism formally recognized as the nation’s fourth official religion, and created the Machar (Tomorrow) conference—a veritable ingathering of Jews from the Balkan nations.In a rented apartment in the capital city of Podgorica, set up as a small synagogue and repository of holy books, some dating back one hundred years, wearing his hat as president of Montenegro’s Jewish community, Jasa Alfandari explained that the nation’s ten Jewish families at the time fled when World War Two broke out. In 1941, Jews from Yugoslavia escaped to Albania which was also under Italian occupation until 1943 when the Germans came in to Montenegro and Albania.

“Montenegro and Albania are the only two countries in Europe, where after the war, there were more Jews (1000) than before (200) the war, with the exception of Denmark because they saved all the Jews, and they had 7,000 Jews before the war,” remarked Jasa.

Of the Jews in Montenegro, ninety percent are Ashkenazim (Jews of European descent), and all are intermarried. “We had a couple of intermarriages and it’s a total acceptance of non-Jewish culture, with no Jewish tradition left in the families.

Jasa himself grew up in a very mixed family. Using the Yiddish word for religiously observant, Jasa said, “My mother’s mother was really frum, a fanatical Jew, who was somewhere from Galicia. My grandfather, my mother’s father originally came from Germany and he was a Bundist, the movement that countered Zionism. They didn’t want the Jews to leave Europe before the forming of the Jewish state. They called Israel “Palestina” and said if Jews leave Europe it would be very dangerous. My father was a Sephardi (Oriental) Jew, born in Belgrade where ninety percent of the Sephardi Jews in the Kingdom of Yugoslavia were fans of Hashomer Hatzair, a distinctly anti-religious movement very active in the state’s early days.

“Can you imagine this house I grew up in? In the morning, my grandmother was teaching me prayers and Jewish things; and then in the afternoon my father and mother were teaching me assignments and about Hashomer Hatzair and leftism. So, I picked up everything. Plus there was no one left from my family, so I grew up alone without anybody,” Jasa explained.

In 1968, Jasa left for kibbutz life in Israel followed by army service as a paratrooper. There, he was an outstanding soldier who participated in many serious undercover operations. In 1991, Jasa left Israel to return home where his elderly mother was ailing. Four children and seven grandchildren live in Israel today.

All the time, Jasa was determined to create a Jewish community, to find the Jews of Montenegro. He visited each family one by one.

“We visited all 300 families. They asked me, ‘What for do I need a community? I’m now 65…okay, you told me that I’m Jewish. Good, so what?’

“I found them through the police, through the election list, through informers. Look I used my knowledge from those years in Israel to scratch out the Jews. I have a neighbor and she asked me not to come to her house. Her brother is the president of a European Jewish community.”

One by one, Jasa began to build a community for the Jews, almost all of whom had assimilated “because they felt no danger.” Almost all knew nothing of Judaism, the rituals, traditions or history.

“We have a Jew here who even has a ‘sefer Torah’ (scroll of the Five Books of Moses) given to him by his mother in his house.”

Jasa sent another young girl to Israel several times and nothing changed, “but after the second time she started to wear a Magen David (‘Jewish star’). Five years before there was no chance, but now…,” he told The Media Line.

Ivana was one of the many people Jasa helped by sending her young children to a Jewish day camp. “My mother and grandmother were Jews but both married Montenegrins. I started to go deeper into Judaism for my children. They will have choices whether to follow or not that I did not have.”

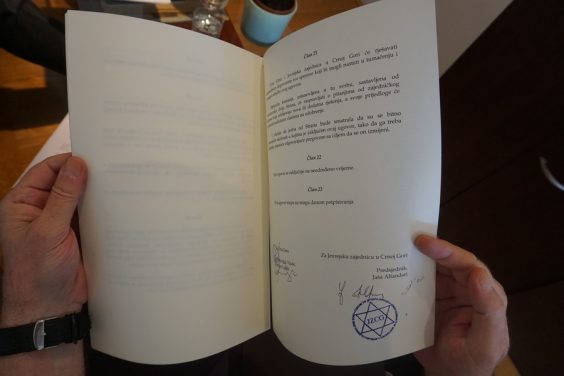

Jasa was proud of what he called the “special relationship between the community and government” citing the official contract with the government that made Judaism an official religion—a document Jasa signed on behalf of the Jewish community. “It’s not like the US. Here it is law. The government officially recognizes us as the fourth religion in Montenegro including the Jewish holidays.”

With a broad grin Jasa explained how he called on former Israeli chief rabbi Yona Metzger whom he had known years ago in the army, invited him to Montenegro and told the government that a chief rabbi is “like a pope to the Jews.” So, a meeting was arranged with the prime minister, the president and the speaker of the parliament. As Jasa told it, “before the meeting the prime minister asked me, ‘So what do I request?’”

He replied, “nothing.” But he added that, “I want recognition of the Jewish religion and the community,” and they said ok.

“Three months later, they called me from the cabinet of the prime minister telling me in three days to be the signature on the contract between the Jewish community and the state.”

A recent addition was Rabbi Ari Edelkopf, a Chabad protégée who was chosen to lead the Jewish community. It was one of Jasa’s final moves to infuse religious rituals and practice into Montenegro, as plans for a Jewish community center and synagogue are underway.

Rabbi Ari Edelkopf, a Chabad protégée who was chosen by Jasa Alfandari to lead the Montenegro Jewish community.

Rabbi Edelkopf grew up in Los Angeles where his father was a Rabbi for many years. He served in Sochi, Russia, until he was one of the rabbis who were deported by President Putin.

Rabbi Edelkopf sat in our meeting that day as Jasa spoke of the 300 people who came to celebrate Hanukkah. “Most of them are Jews and they never stepped foot into the community. But they came to see the rabbi and sing songs and lay the cornerstone for the synagogue.

The synagogue and Jewish Community center will stand on prime property donated by the government, right next to the Turkish Embassy. “It’s the most expensive land in Podgorica,” Jasa boasted. “Plans call for a 500-seat center. Such a center, such a place does not exist in the Balkans.”

As the synagogue’s building plans were moving along, Rabbi Edelkopf and his wife decided to celebrate their son becoming a Bar Mitzvah with the Montenegro community. What the Edelkopfs believe will be a first, the festivities will take place in a hotel in Budava City, the same venue that hosted “a real Seder (Passover celebratory meal) with kosher food!”

Six years ago, Jasa created Mahar (which in Hebrew means tomorrow) whose goal is “to teach to those who do not even know what Israel is.” This year’s special guest for the three-day event in October, celebrating Israel’s 70th anniversary, at which more than 500 participants are expected as in previous years, is legendary Israeli general Avigdor Kahalani. Jasa summed up the purpose of Mahar by telling us that, “I don’t know if you can believe that on the first Mahar six years ago, 50 percent of the participants didn’t know the Israeli national anthem, Hatikva. Now, everyone knows Hatikva. It’s enough for me.”

Jasa’s parting words are just the beginning of what lies ahead for the Jewish community leaders. Jelena Djurovic, who is one of the founding members of the community and a vice president says that it is still a mystery how Jasa found her years ago. A politician and a journalist professionally, Jelena’s family was prominent in Balkan life. Her late grandmother was Lotika Zellermeier who was the inspiration of the main character of Ivo Andric’s noble prize-winning novel The Bridge on the Drina, a story about the Jews of Bosnia.

But, Jelena only was told she was Jewish at 11 years of age when the book was about to launch. Her grandmother forbade her mother to disclose her identity until the last moment because people in the community were not aware her family was Jewish.

Government contract signed by Jasa Alfandari recognizing Judaism as an official religion in Montenegro.

“We grew up in a completely non-Jewish home and we lived together because my grandmother lost some part of her family in Belgrade and some in Dachau. In 1936, she obtained false papers to keep herself and her parents alive and were able to move to Belgrade without being recognized as Jews because we had money.

“’Until I am alive you cannot come to be involved in anything’ Jewish my grandmother told me. And the next 13 years, while my grandmother was alive, I became Jewish but not on the outside. This is irrational, but I needed to fulfill her wish.

From the moment my grandmother died I started wearing a Magen David and never took it off. My mother helped me understand more about religion, politics, history and the Holocaust.

“Today we have 300 members of the Jewish community and we have a rabbi. People are getting in touch, people didn’t practice religion and even more complicated didn’t know they were Jews. We need to take baby steps. We now have a full house of up to 150 people for Rosh Hashanah and Yom Kippur,” she told The Media Line.

Jelena is still in shock over Jasa’s sudden death. She called him a substitute father, a mentor, teacher and friend. “I can never express what he meant to me. I was ten years old when my father, a Montenegrin and famous lawyer died,” she said.

The community will now need to divide the tasks and determine who will be the president after the Mahar conference in October. They are looking toward their partners, The World Jewish Congress, the Euro-Asian Jewish Congress, and Jewish National Fund to assist them in moving forward.

Hana, Jasa’s youngest daughter, told The Media line that her father established two other Jewish communities in the Balkans: Albania and Kosovo, bringing 150 and 100 Jews into the open. Hana explained that, “It means Jews living here forgot who they are and pushed people to see if they had Jewish roots.

“Growing up I knew I was special but I was not connected with other families. It changed when I was 15, when we started celebrating holidays, learning about tradition and today we have a Rabbi. I don’t feel alone anymore.”

His daughter’s description of her dad reveals the strength and other attributes that one would need to seek out and reunite the “missing” Jews in three nations.

“My Dad was a simple man who started from the bottom. He hunted Nazis in South America, Argentina, Uruguay, and Venezuela. He was like the Europeans (didn’t look Jewish), fluent in 12 languages including Arabic and German. He was basically an undercover spy acting as a German who was able to disguise himself in the German Nazi communities in South America.”

As the community plans its memorial for Jasa, all agree it will take several to do his “work of one” and that the greatest tribute will be to continue his work. Co-vice president Giorgio Raicevic is temporarily filling the office of president of the community.

As daughter Hana told The Media Line, “We cannot replace all the great things he did, we can just follow his path and it is an honor to do so. Mahar will continue, the synagogue will be built and the Jewish community will continue to exist. We will continue to carry his torch. We need to make him proud.”

Article written by Felice Friedman

</span>

Reprinted with permission from The Media Line

Finding the Jews of Montenegro: One man’s mission : https://ift.tt/2O7DHqD

No comments:

Post a Comment